Selecting the research methods

When selecting appropriate research methods for studying oTPD programmes, there are a range of considerations to be made. This section summarises the methods selected for this study including strengths and limitations of the approach. This is offered on the following two pages in a discussion of using design-based research (DBR) as well as the research phases and approach to data collection and analysis.

Studies should offer a detailed rationale for their research, clearly define the research context, and articulate the paradigm and theoretical framework that underpins the research. For this study, I opted for a research worldview instead of a selected paradigm, which incorporated a pragmatic set of philosophical assumptions of the nature of knowledge as socially constructed and a product of human interests (Habermas, 1968; Freire, 1970), elements of critical realism and theory (i.e. change theories that help with creating practical improvements and changes), non-representational theory in order to focus on practices instead of studying and representing social relationships (Thrift, 2008; Dewsbury, 2000; Merleau-Ponty, 2002)

As you review the content in these sections, reflect on the following:

- What are the ethical dimensions for research of this nature?

- What limitations continue to subsist in the methodologies utilised in this study and throughout the sector more widely?

- How can we collect more meaningful data through leveraging the affordances of big data and technology-based analysis software and communities?

Research questions

This study was guided by three main research questions:

- How can technology afford new forms of dialogue to support the development of a teacher community of practice in which practitioners reflect together, support one another, and share practice?

- To what extent can a mechanical MOOC afford opportunities to enhance dialogue between in-service teachers within an inquiry-based TPD programme?

- What are the key enablers and barriers for the use of dialogic pedagogy in oTPD programmes?

- What influences a teacher’s participation in online peer dialogue?

- How do in-service teachers perceive and experience online learning in reference to their professional development?

- What design principles help to make the model scalable and sustainable?

The theory of change at the outset of the study was:

If teachers build a dialogue with one another within online TPD programmes, through reflecting together, sharing resources and supporting one another, they will form a sustainable community of practice, which will enhance their use of dialogic teaching in the classroom.

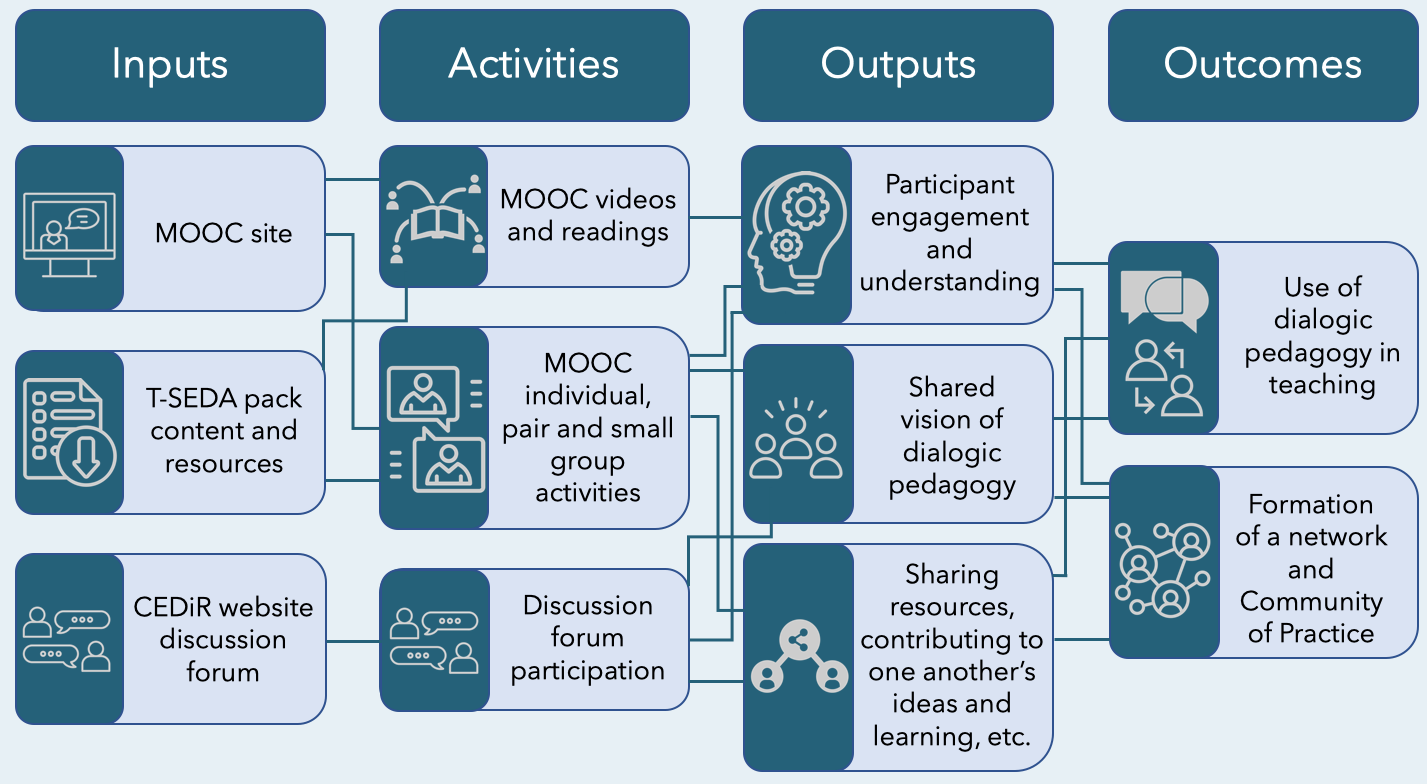

To test this theory of change, the MOOC series was designed, trialled and assessed as the intervention. Below is a visual summary of the logic model of this intervention.

The literature supported this initial theory of change, evidencing connections between the inputs and outputs, but the intervention went beyond the evidence to fill a theoretical, methodological, and pedagogical gap where there is currently a need for accessible, effective, sustainable and scalable professional learning opportunities and underpinning theories that may explain what works well and what does not.

Inputs included:

- The MOOC host site via github

- The T-SEDA toolkit contents and materials including additional materials produced by the Cambridge Educational Dialogue Research (CEDiR) team

- Discussion forum via a resource website, edudialogue.org

The activities that were developed from these inputs included:

- Video tutorials and readings

- Individual, pair and group work activities

- Discussion forum contributions These activities did not seek to transmit knowledge regarding standardised uses of dialogic pedagogy, but rather developed resources and activities for local contextualisation to support its use, as emphasised by Hennessy et al. (2021).

The outputs from participation in these activities included:

- Participant engagement and understanding through reflection and creation

- Developing a shared vision of dialogic pedagogy

- Sharing resources, contributing to one another’s ideas and learning, and other forms of peer support.

Building on these outputs, the outcomes that came from this intervention included:

- More effective use of dialogic pedagogy in practice

- The formation of a peer network and community of practice.

Areas of impact include:

- Sustained usage of resources and a dialogic approach at a local level

- Metacognitive growth for practitioners

- Sustained participation in a community of practice.

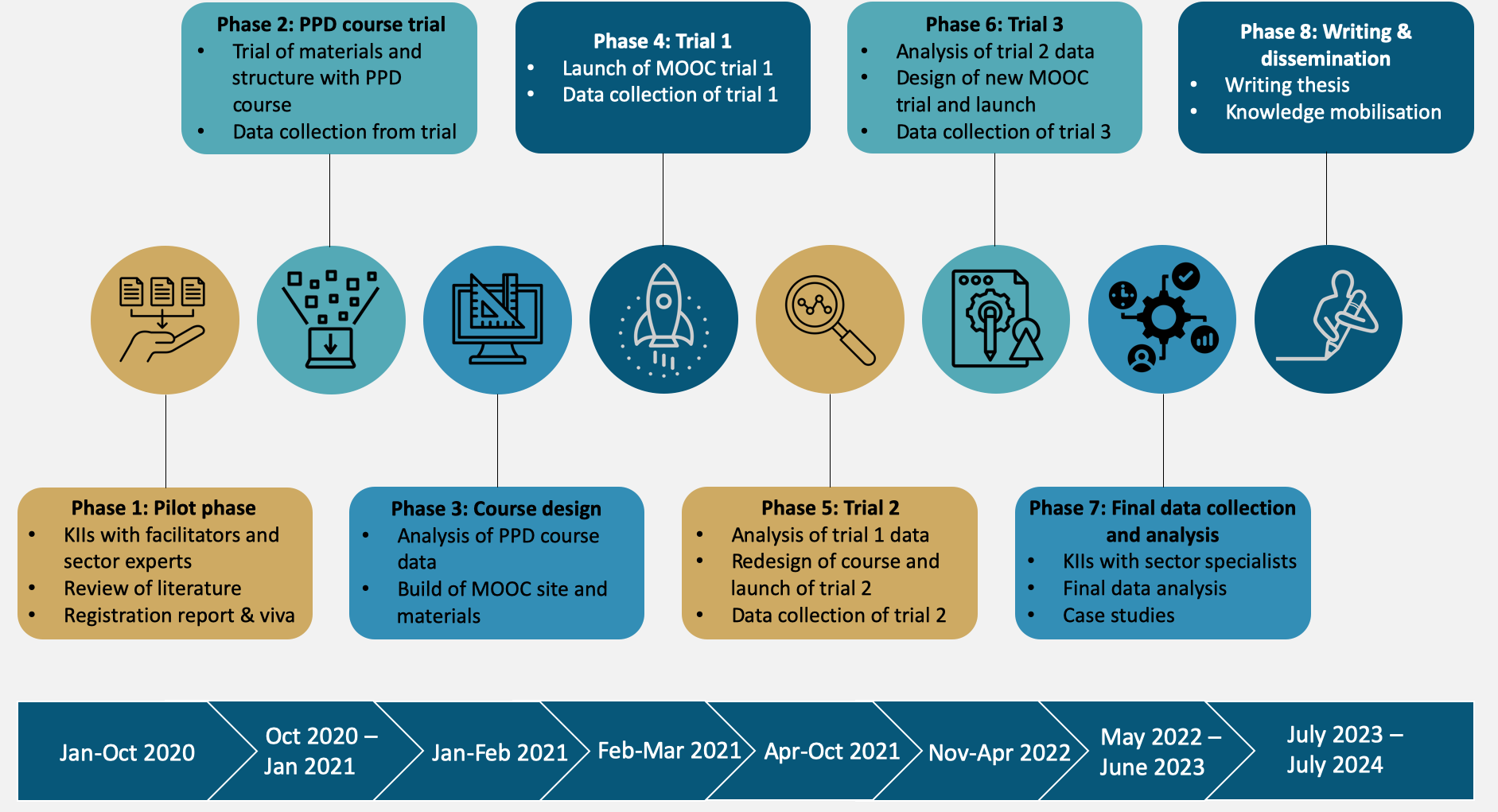

Research phases

The study followed eight empirical research phases. Because of the iterative nature of the study’s design, analysis was conducted between trials of the intervention. A participatory focus cut through all research phases. The following figure offers an overview of these 8 phases and associated timelines.

Pilot research was conducted during phases 1 and 2. Phase 1 included a literature review and interviews with local facilitators that had previously participated in T-SEDA inquiries as well as sector specialists. Phase 2 built on these findings through involvement in and monitoring of an online Practitioner Professional Development (PPD) module entitled ‘Educational Dialogue’ offered by the Faculty of Education as part of the (Year 1) Transforming Educational Practice pathway. This was an opportunity to trial the online discussion forum and resources and analyse engagement in online TPD, particularly because this module had to be moved to a fully remote offering due to Covid-19 isolations in effect. This phase provided an additional opportunity to pilot the proposed research methods to ensure that they were appropriate, relevant, and elicited useful and insightful data.

Drawing on the pilot research findings, the design of the MOOC was finalised during Phase 3 in dialogue with the T-SEDA team and with the support of the Online Learning Services Department and Cambridge University Press. Following the design phase, the intervention was tested during Phases 4, 5, and 6. Phase 4 saw the launch of Trial 1 of the intervention (Courses 2 and 3 of the MOOC series) over 6 weeks in February-March 2021 and the collection of associated data. Phase 5 began with an analysis of data from Trial 1 and a redesign of the course where required, and followed this with the launch of the second trial of Course 3 (October-November 2021) and associated data collection. Phase 6 similarly began with the analysis of data from Trial 2 and redesigned the course accordingly. A new course, Course 1: ‘The Fundamentals of Educational Dialogue’, was developed based on the data analysis, which was trialled (February-April 2022) and associated data were collected.

Phase 7 involved final data collection from sector specialists and analysis that went beyond the analysis conducted in between trials of the intervention. The data was interrogated with further questions regarding outcomes, impact, sustainability and scalability. This culminated in three publications and three additional case studies. The research was written up, in full, in Phase 8, during which the dissemination plan was finalised and enacted. A central tenet of design research is the careful dissemination of research findings for future use of researchers to build on as well as for practitioners’ use. This is expanded on in Section 3.7, when discussing the ethical need for mobilising research findings in an accessible, clear, and meaningful way. The dissemination plan (Appendix A) was finalised in conversation with participating educators to ensure that the information was presented in a helpful and engaging manner.

Positionality

By positionality, I refer to my worldview and ontological assumptions about what I think is knowable about the world, my epistemological assumptions regarding my beliefs about the nature of knowledge, as well as my assumptions about the way humans interact with our environment (Holmes, 2020). My assumptions and experience working in the sector as well as my position as both researcher and course designer and facilitator have undeniably influenced how the research was conducted, its outcomes and results. This was mitigated where possible through user-centred design activities, and keeping detailed reflective logs throughout the research process, encouraging both self-reflection and a reflexive approach to identify, critique, and continue to articulate my positionality. These logs were largely unstructured, stored in one document that kept notes from the course trials (e.g. notes from live sessions, reflections regarding uptake of tools and resources, informal feedback from participants and colleagues within CEDiR, etc.) as well as notes from the literature and reflections on the research methodology.

Reflecting on my dual role as researcher and educational consultant, my motivation for my PhD research is consistently fuelled by my consulting work as I bear witness to weaknesses in the sector that drove me to pursue my own research project in the first place. This is both a privilege to be able to draw on this passion, and also a challenge in that I struggled not to be disillusioned by the sector findings as I conducted evaluations for EdTech programmes in low-resource contexts. Related to this dual role, I have been able to draw on the skills and competencies I use in my consulting work but this also means that I have to be constantly aware of my default to fall back on technical perspectives instead of the theoretical. This has required continuous reflection to ensure that I am engaging with my research findings at a more critical and theoretical level.

As a practitioner from and within the Global North, I acknowledge this research and the course series I developed may exacerbate the very research and practice divides I seek to explore. This research only includes voices from participants who were able to register and participate in an online course, inadvertently excluding the voices of the most marginalised educators. Also, the courses provide tools created by a team at an elite UK-based university. This is the current context of MOOCs (i.e. delivering content created and curated by Western academic institutions) and while it may be helpful for this research to be used by similar courses, it is also important to acknowledge this research does not seek universal truths in experience for similar courses to use as generalisable. Rather, the objective is to open up discussion for further reflection for other studies to build on, critique and address. This conflict and challenge is woven throughout the findings and remains an important area of further research.