Data collection and analysis

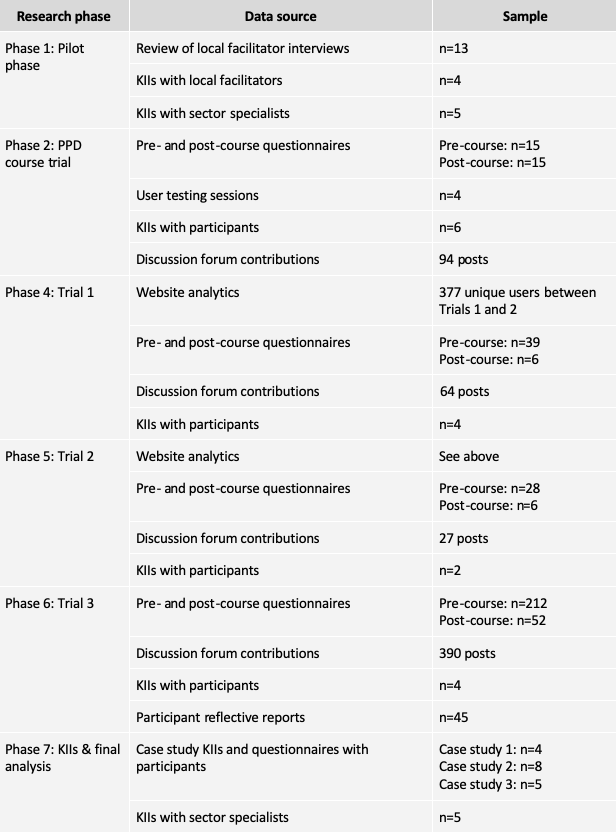

Data collection and analysis took place throughout the first seven phases of the research in a parallel mixed design whereby quantitative and qualitative research strands occurred simultaneously in a parallel manner (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). The following table provides a summary of data collection sources and sampling approaches, by research phase.

The pilot research in Phase 1 built on the findings from a 15-month trial with the T-SEDA toolkit led by Hennessy and Kershner, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Impact Acceleration Account (IAA). This trial included 74 teachers across 9 countries based in 15 institutions. Participants’ teaching contexts varied widely and included early years and primary education, secondary education, further and higher education. The study leads provided permission for their project data to be analysed and related findings are featured in Hennessy et al. (2021).

A systematic analysis was conducted of responses to selected questions from 13 interview transcripts and notes that had been conducted with local facilitators between March and May 2019 as part of the data collection for the IAA T-SEDA trial. These interview transcripts also included translated interview notes for two facilitators whose original interviews were in Spanish.

All transcripts were read with the research questions as guidelines, and new findings that emerged from the analysis were documented and compared with existing findings from previous analyses of interview data by the T-SEDA team, documenting confirmation and counter-examples throughout. Transcripts were analysed in Excel because of the small sample size and amount of content. Responses were gathered related to the relevant questions in separate analysis spreadsheets, coding by question number and then by emerging theme. This required a few rounds of coding. If the questions were out of sequence, search terms were used to find relevant content including: ‘adapted’, ‘resources’, ‘website’, ‘model’, and ‘sustain’. The names of facilitators were removed for any quotes included in the findings section in Chapter 4.1 and these findings are referred to as the ‘2019 interview transcripts’ for clarity regarding the data source.

Following the analysis of the transcripts, KIIs were conducted with four participants from the IAA T-SEDA trial, based in England (n=2), Mexico (n=1) and New Zealand (n=1). These facilitators also had transcripts or interview notes that were analysed in the above systematic analysis to triangulate findings. The purpose of these interviews was to elicit their insights and recommendations regarding the translation of the materials into an online format. These interviews lasted between 30 and 45 minutes and took place over Zoom or Google Meet, depending on the preference of the participant. The interview template is included in Appendix B, although questions were tailored according to their previous interview transcript in order to avoid repetition and to build on previously shared insights.

KIIs were also conducted with five specialists in the field to discuss MOOC provision for TPD programming and elicit expert guidance regarding good practice. These conversations were informal and involved snowballing, whereby a conversation with one person would lead to another. The specialists were individuals who had worked with MOOCs extensively, including four individuals responsible for developing and administering MOOCs and one individual who provided university guidance for MOOCs and online learning more broadly. These interviews lasted between 30 and 45 minutes and took place over Zoom or Google Meet, depending on the preference of the interviewee. Conversations were largely unstructured and framed according to the individual’s work and area of expertise. A guiding template is not included as an appendix because the questions differed greatly from person to person. All interview content was analysed using the same process as the systematic analysis in Excel, with transcripts coded by emerging themes using constant comparison methods. Related to these conversations, this phase also included detailed discussions with other PhD students who were undertaking similar studies to hear about their research processes; in particular, successes, challenges, and initial findings.

Phase 2 of the research saw data collected from the PPD course, which included: (i) pre- and post-course questionnaires (see Appendix C for questions); (ii) user testing sessions regarding the edudialogue.org site’s functionality, engagement and contribution to a sustainable community of practice (see Appendix D for framework); (iii) KIIs with participants to elicit insights regarding oTPD materials and courses (see Appendix E for template); and (iv) discussion forum contributions. This was very similar to the data collected during Phases 4, 5 and 6 following each of the course trials, which included pre- and post-course questionnaires (see Appendix F for questions), website analytics (for Trials 1 and 2 of the course), KIIs (see Appendix G for template), and discussion forum contributions. This also included the reflective reports submitted by participants at the end of Trial 3 of the course, which were analysed for Case Study 1 (see Appendix H for report template).

Questionnaires were sent to participants in all course trials at the beginning and end of the course. The questionnaires for the PPD course were circulated via the Faculty-licensed survey software ‘Qualtrics’ while the questionnaires for the MOOC trials used Google Forms. Convenience sampling was utilised. The pre-course questionnaires gathered demographic information as well as participants’ prior experience with educational dialogue and online courses for professional learning. The post-course questionnaires posed questions regarding engagement in the course, the efficacy and relevance of the structure and content, and the impact on practice. It included appropriate skip logic to ascertain whether the participant finished the course. If not, associated questions regarding their drop-out were included. Additionally, the questionnaires included a rating scale for teachers to assess their use of dialogic teaching before and after the course. These questionnaires were voluntarily submitted (i.e. it was not a requirement for enrolment or completion), although reminders were sent to cohort participants by email and on the discussion forum to encourage their completion.

The questionnaires were matched by Participant ID for analysis, and were analysed using descriptive statistics, which explored participant demographics, their behavioural and cognitive engagement in the course (i.e. what they did and what they learned), and recommendations for course improvement. According to Teddlie and Tashakkori (2009), descriptive statistical analysis is “the analysis of numeric data for the purpose of obtaining summary indicators that can efficiently describe a group and the relationships among the variables within that group” (p. 24). Correlations were identified between data or clusters within the data which represented learners with similar characteristics. Factors were identified in the data, which related to their engagement, in order to better understand the features of the course that required modification.

For the first two trials of the MOOC, website traffic and usage data from site users was collected via Google Analytics. This included page clicks and heat maps of different levels of engagement and activity. This data was analysed using descriptive statistics to explore behavioural engagement with the course materials, triangulated by the questionnaire responses and KIIs. A visual representation was produced of how users move around the pages of the website by showing its most and least popular elements. It was not possible to track the specific activities of each user as a sign-up system was not utilised in order to see the course content. This was intentional to remove steps to join the community. This data therefore summarised user experience more broadly, and made triangulation of this data source with others imperative. This was also used as a data source for site improvement. This data was not collected for the third trial because of concerns regarding privacy and bandwidth usage (see Section 3.7 for further information regarding this decision).

KIIs were conducted with a selection of participants following the end of the PPD course and each trial of the MOOC. This used purposive sampling. Interviews were semi-structured and audio-recorded following permission from interviewees, transcribed, and prepared for analysis. They aimed to elicit details regarding user experience, engagement, and impact on practice. Templates for the KIIs were based on the pilot phase template and refined in Phase 2 of the research. KII transcripts from interviews with course participants were analysed thematically using constant comparison methods. This was largely inductive, exploring the data for patterns, themes and categories and deriving codes from the data and not having a predetermined set (Guest et al., 2012; Hilliard, 2013; Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). In Phase 7, a combination of interviews and questionnaires were conducted with participants using purposive sampling for the case studies (see Appendices I-K). Interviews were also conducted with sector specialists using both purposive and snowball sampling to elicit further insights regarding oTPD futures, community of practice engagement, impact, scalability and sustainability. As above, these ranged considerably based on the informant’s background and experience and so a template is not provided. Broadly, these discussed design considerations, continued barriers, and the future of oTPD. Analysis was conducted using the same approach as for the KIIs with participants. This analysis has been distilled into the case study findings and is also featured in Section 5.3. Discussion forum data comprised original discussion forum contributions from participants, their responses to others’ posts, and their ‘likes’ of posts. Frequency counting was used to understand engagement levels on the forum.

Using mixed methods analysis, data were aggregated across all sources whenever possible to provide a rich picture of usage and engagement. Mixed methods data analysis “involves the integration of the statistical and thematic techniques” (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009, p. 27). Triangulation between data sources was also employed, which refers to the combinations and comparisons of multiple data sources, data collection and analysis procedures (Ibid). This also included reviewing my reflexive accounts, which I kept throughout the trials of the MOOC series.

Both Excel and R were used for quantitative analyses (closed questions from the questionnaires / website analytics / discussion forum posts) and NVivo was used for qualitative analyses (open-ended questions from questionnaires / KIIs / reflective reports). Dedoose was used for the qualitative analysis conducted for the joint working paper (i.e. Case Study 2), which was selected for its cloud-based software to make collaboration easier.

Following data analysis, data quality was assessed, considering both ‘inference quality’ to evaluate the quality of conclusions made as well as ‘inference transferability’ to explore the degree to which the conclusions may be applied to other contexts (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). This also included participant validation of the findings through member checking, whereby participants were asked to review results to ensure they were accurate and reflective of their experiences (Birt et al., 2016).

Addition of case studies

Three case studies were conducted to explore key themes in more detail. These were not included in the initial research design, however following data analysis from the three MOOC trials it was clear that these themes required richer data to reach saturation and adequately represent participant perceptions and experiences. Case study methodology (Hamilton, 2011) was used in order to build a full picture of three themes, drawing on in-depth insights, perceptions and experiences of participants. This included leveraging the available data that was already collected to triangulate further data collected, to strengthen the validity of the findings.

Case Study 1 explored the local impact of a global MOOC. The aim of this study was to better understand the impact of the MOOC on practice, particularly considering the different ways this manifested in differing contexts. Because of the part-time nature of the PhD, this study was able to follow up with participants two years after taking the first MOOC trial. This case study utilised responses to the pre- and post-course surveys as well as additional KIIs and questionnaires with four participants from three different countries (the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, and Iran). In addition, this study drew on findings from the reflective reports submitted as final learning products for the third MOOC trial.

Case Study 2 utilised phenomenology to explore teacher perceptions of and experiences with online TPD. The aim of this study was to better understand the real, lived experiences from participants in a richer way, including how they perceived online learning for their professional development. This utilised pre- and post-course survey responses and conducted two focus group discussions (FGDs) with a total of five participants as well as eight additional KIIs to elicit further, detailed reflections and insights from participants.

Case Study 3 explored issues regarding the reach and equitable access to oTPD. While the MOOC series was not specifically designed for participants in low-resource contexts, this was still a central consideration during the build of the course series and the data collection and analysis. Within the design principles, equitable access continued to emerge as a critical consideration regarding both the course content and structure; i.e. who is able to access and meaningfully engage in the materials and who is not. This case study aimed to provide a deeper dive into this area and explore the affordances that MOOCs can realistically provide to educators globally and what the barriers are to participation, as experienced and articulated by participants. This study utilised available data from the pre- and post-course surveys and conducted additional KIIs with five participants who were from Iran and Sierra Leone.

Ethical considerations

Various ethical dimensions exist to educational research. This research study sought to engage in ethical decision-making through “an actively deliberative, ongoing and iterative process of assessing and reassessing the situation and issues as they arise” (BERA, 2018, p. 2). Ethical and participatory research was promoted at all stages of the study through adherence to the Faculty of Education Ethics Guidelines and BERA’s Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (4th ed). The most relevant guidelines for this study are discussed below, alongside actions for how the guidelines were implemented. Publications also note ethical considerations regarding the research specific to those methodologies, and all data collection tools are also available, including an overview of related informed consent.

Preparation and design of intervention

Prior to submitting the registration report for this study, a risk assessment and a Faculty ethics checklist were completed, approved and logged with the Higher Degrees Office, in addition to the ethics checklist submitted for the pilot phase of the research. The risk analysis reflected on how an ethic of respect for different stakeholder groups was considered in the research design. This included such considerations as the time and effort that participation in research can require. In addition, it was critical to build my own competence in the field (prior to engaging in research activities) through: (i) conducting an in-depth registration report that encompassed a comprehensive review of literature, (ii) undertaking a pilot research phase to ensure the relevance of the project, (iii) articulating intended research methods alongside justification for their use, and (iv) training in relevant educational research methods.

Following the initial pilot research and the completion of the registration report and viva, I used the PPD course to test digital content and resources as well as the discussion forum. Ethical considerations were similarly applied to the data collection for the PPD course, including voluntary written consent for the use of participants’ data for this PhD research as well as a consent and participant information form specific to the discussion forum. Participants were given my contact details in case they required further information about the research. This research used data of paid participants in a PPD course to inform a MOOC that is open and free to take, and therefore it is also worth noting that the MOOC does not offer the same advancements and certification that the PPD course does, nor does it offer the same level of support by University of Cambridge instructors and the institution (e.g. use of the Faculty library). Rather, the MOOC has been conceptualised as an opportunity for continued teacher inquiry and the trialling of open source software to provide and promote this widely. In addition, certification was provided by the CEDiR research group specifically instead of the Faculty or University and this was clearly articulated at the outset of the course and on the certification itself.

Ethics was also part of the course content design, going beyond applying ethics in this study and additionally encouraging research ethics in inquiry for participants of the MOOCs.

Implementation and assessment of intervention trials

The study ensured that all participants were treated “fairly, sensitively, and with dignity and freedom from prejudice, in recognition of both their rights and of differences arising from age, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class, nationality, cultural identity, partnership status, faith, disability, political belief or any other significant characteristic” (BERA, 2018, p. 6). This included sensitivity and attentiveness towards structural inequalities.

Consent is a critical part of ethical research, and voluntary consent was obtained for all data collected. Participant information and consent forms were read, discussed and agreed before data collection took place. The consent process ensured that participants fully understood what their participation meant, including information about the researcher, the research focus, the details of their participation, their right to withdraw at any time, how confidentiality was ensured, how their data was kept including appropriate security measures, and for what purposes their data was going to be used. Participant consent forms and research information sheets for data collection are included in their associated appendices, which drew on resources from the Faculty and the University of Cambridge Research Integrity department. Completed forms were retained in a secure folder on the personal Google Drive used for this research.

Because this research engaged with online data, if authors of posts or other material withdrew or deleted data then that data was not used. Because it was not possible to identify such withdrawals after data had been harvested and analysed, a proviso was offered that the data were ‘as made available to the researcher at the [stated] date of harvesting’.

Prior to data analysis, participants’ data was anonymised, in line with the consent agreement they signed. All data was stored securely through the use of password protection. Data storage and use complied with the relevant legal requirements as stipulated in the UK by the Data Protection Act (1998), General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and subsequent similar acts. Throughout the length of this research, this has been revisited to ensure compliance with any changes in data use regulations and guidance.

When considering safeguarding my own physical and psychological wellbeing while conducting the research (as per BERA guidelines), I was able to draw on and leverage skills from my years of experience working in various challenging and pressurised contexts and environments including the feeling of isolation that a remote-based study can involve. I had the requisite skills to undertake work of this nature and was confident in my experience and with the support of the Faculty, especially from my supervisor.

Writing and dissemination

During the writing, key ethical considerations for this study included reporting all findings, regardless of whether they were negative and writing up participants’ data confidentially and anonymously in line with the consent agreement. There has also been appropriate attention paid to using the correct citations and attributions throughout, which is an ethical tenet for all research to adhere to. Lastly, this study has prioritised knowledge dissemination from the outset and this phase ensured that research findings were written and disseminated in an engaging, clear and concise manner for all stakeholders to access and engage with. This included the development of an online course that displays the findings from this research in order to come full circle and offer a course on conducting research regarding course-based educational interventions.

Limitations

The study faced a range of challenges and limitations, which are presented in reference to the research context, the intervention, and the research design. Ways in which they were mitigated throughout the research phases of the study are discussed in turn. Anticipated risks and limitations were similarly included in the risk analysis that was submitted to the Higher Degrees Office during the registration phase of the research. Note also that limitations are presented within the findings in Chapters 5 and 6, specific to the publications included.

Research context limitations

A number of contextual limitations were faced, particularly related to Covid-19, which deeply affected the first five research phases of this study. This resulted in the need to provide a fully online TPD course (instead of a blended option, for example), collect data remotely, and all within the context of a pandemic, which had its own effects on participants and myself. How these limitations relate to educators is discussed in this section, with particular attention to educators’ digital skills, their availability, and the relevance of resources.

Educators’ digital skills and interest in using online formats for professional development were varied, and dependent on their prior experiences with technology. The first two phases of the research sought to develop a relevant, meaningful and user-driven design for the MOOC to create more interest and excitement in the programme. Because of the need for strong internet connectivity as well as digital skills to access the online course and interact with other participants, however, the design undoubtedly excluded some populations who, for example, did not have access to the infrastructure and skills required to participate. This was particularly the case in low-resource contexts where a range of barriers to MOOC participation have been well documented (e.g. see Liyanagunawardena et al., 2013). This was considered in more detail during a review of participant demographics from the pre-course questionnaire responses, and a follow-up case study (Case Study 3) that explored equitable access for online TPD.

The availability of participants to engage with and complete an online TPD course was another limitation. Educators have to balance multiple demands and competing priorities, in addition to living with extreme circumstances during Covid-19 and the challenges it created in their professional and personal lives. While the context of Covid-19 presented an urgent need for rigorous evidence-building of remote TPD programming that is flexible in its design, it is also likely that many educators were not in a position to embark on professional development at an otherwise difficult time. The first phase of the research considered this carefully and the length and intensity of the course were assessed in relation to the capacity of participants. This was revisited in the second and third trials, although each subsequent trial had fewer pandemic-related restrictions taking place globally.

Linked to this are the challenges regarding participant retention, which is notoriously low for MOOCs historically. This was carefully considered in the first phase of the research, the mechanical MOOC structure was leveraged, and data were collected and analysed with regard to scalability.

Limitations regarding the relevance of resources as well as challenges associated with the translation and localisation of materials were also present, however these were not as common as is usually considered for MOOCs. This may be because participatory research and collaboration with practitioners on contextualising resources was a critical part of the first research phase and part of the overall flexibility in both the MOOC structure and content. It was critical for participants to be able to adapt resources themselves according to their needs and context with ongoing support on how to do this. Where challenges arose, these were documented through feedback from participants during course questionnaires or in conversation during live coworking spaces.

Intervention limitations

Limitations regarding the intervention itself (i.e. the MOOC series) included technological and engagement challenges. Technological limitations included the usability of the website and platform. Piloting the model during the PPD course and conducting user testing sessions were important steps in mitigating many of these challenges. A user guide was produced to assist new users in navigating the platform, and the course was intentionally designed to reduce the number of clicks required to move throughout the course pages. Technological limitations also included the length of time required for me to build the course and test the functionality. This was not as much of a challenge for the github site as it was for building the edudialogue.org site, which required significantly more time than anticipated to coordinate with a site developer and bring the forum to a high quality standard that was user-friendly and engaging.

Engagement limitations included participants’ engagement in the course structure and materials, as well as within the online discussion forum, and their retention in the course. Participants reported that the biggest barrier to their engagement was their availability with having to balance multiple personal and professional demands. While this was mitigated to some extent through the flexibility of the course design, it was a constant balancing act of presenting enough information to build understanding and momentum without too much that it made it overwhelming for participants. Having a ladder of support available for participants to access helped with both these sets of challenges, however there was still a significant drop-off in numbers of participants from the course registration to those who completed and submitted final learning products. This is an area for future research to consider more fully, however, because of the lack of understanding of the experience of the ‘inactive’ participant. In addition, it is noteworthy that the small groups of engaged participants within the courses (i.e. those participants who attended the live events, posted on the forum, etc.) who began the courses typically did complete them, indicating that motivation from the outset to engage resulted in a higher likelihood of completion.

Research design limitations

Research design limitations included the complexity of the study, the lack of a control group, the ambitious timeline, and working with significant amounts of data. The study had many human, cultural, political and environmental factors that could not be controlled, which made this a difficult but worthwhile (and fascinating!) research undertaking. The methods sought to be varied in order to capture as many of these moving parts as possible, and the research approach ensured that the practice was grounded within theory.

While a comparison group was not used for this research, comparisons across conditions are rare in design research and comparison is typically done within or between design cycles (Bakker, 2018). There were three research cycles and a thorough review of prior research for this study. This study drew on previous examples of design research studies that employed iterations instead of control groups to inform the design.

Large amounts of data were derived through different means, which created time constraints and difficulty in ensuring that all data was utilised. A generous amount of time was allocated for each research task and the part-time structure of the PhD allowed for additional flexibility to spend more intensive periods of time in certain weeks where needed and less time in others to achieve an appropriate balance. In addition, careful consideration was made regarding the ethics with the format of the course being fully online. While it can be difficult for participants to understand how and for what reason their information is being used in some online courses and on some websites and apps, this was intentionally very clearly outlined for users.

All data was collected remotely, which offered particular challenges for qualitative data collection. I was able to draw on learning regarding remote data collection, including the ways in which my consulting work that I pursued outside of academia had to pivot to remote data collection in April 2020 when Covid-19 resulted in widespread quarantine. I continuously sought best current practice through an ongoing review of relevant academic and grey literature and attendance at interactive webinars (hosted by NVivo, GEC, etc.), made accessible through my consulting work. Similarly, I continuously contributed to the ongoing global dialogue through active participation in forums, webinars, and online conferences, with the aim of strengthening the sector’s collective understanding of how to conduct qualitative research during a pandemic. It was also important to remain agile, responsive and willing to embrace change. This included making adaptations where needed to the course design as well as to data collection based on systematically capturing successes and challenges throughout the multiple iterations of the research. It was critical to use participatory approaches in the design and implementation of the methodology, as this resulted in more relevant tools and more meaningful responses from participants. Lastly, building rapport during distance-based interviews was challenging, but success was seen with using a platform that was preferred by the interviewee, being flexible to talk at a time that was most convenient for them, ensuring that a long enough interview time slot was scheduled to allow for initial conversation, and having a series of probes (i.e. primary and secondary interview questions with probes if needed to draw out relevant information) in case the conversation became stifled because of connectivity challenges or the respondent’s discomfort in interacting online. Interviews conducted during the pandemic (particularly during 2020) also benefited from employing trauma-informed methodology whereby the beginning of the interview explicitly acknowledged the difficulties imposed by Covid-19 and left space for associated discussion if led by the participant.

Another challenge was due to the use of a mechanical MOOC model, which emphasises removing as many barriers to participation as possible. This meant that none of the content from the course was locked and participants did not need to register in order to access the course materials. Because the questionnaires were voluntary, it was therefore not possible to know whether more participants were engaging in the course inactively.

Changes to the research design were made based on ongoing reflection and assessment of the quality of the tools and their associated data. Minor changes include adapting the pre- and post-course questionnaires to be clearer in the questions posed and similarly adapting the semi-structured interview templates. Major changes to the research design were the addition of case studies and the removal of website analytics from the third iteration of the course. Three case studies were included in the research design to explore key themes (longitudinal impact, educator perceptions of and experiences in oTPD, and equitable access) that were not saturated through the initial data collected. A legacy survey was developed and circulated to participants to elicit this information, however this received a poor response rate. The case studies were therefore designed and used to provide deep dives into these themes, whilst drawing on the wider data for triangulation.

Google Analytics were used to track website user pathways through the course site. It was decided that this would not be used for the final trial due to connectivity issues participants were experiencing. Through further research, I found that Google Analytics is subject to blocking and JavaScript concerns. In addition, the use of the analytics from the first two trials provided enough data to understand how the site was being used to modify its design as required. I was also uncomfortable with the amount of data generated by Google Analytics and while I did not access it in full, privacy risks easily outweighed the advantages of collecting more website analytics for the final trial.