Findings

The participants

The findings draw on data from four courses. The first is a practitioner professional development (PPD) course that was featured in the pilot research. Then there are the three courses from the MOOC series. Below is an overview of the number of participants who filled out a pre-course survey for each trial.

- Pilot research (PPD course): 15 participants

- Trial 1: 39 participants

- Trial 2: 28 participants

- Trial 3: 212 participants

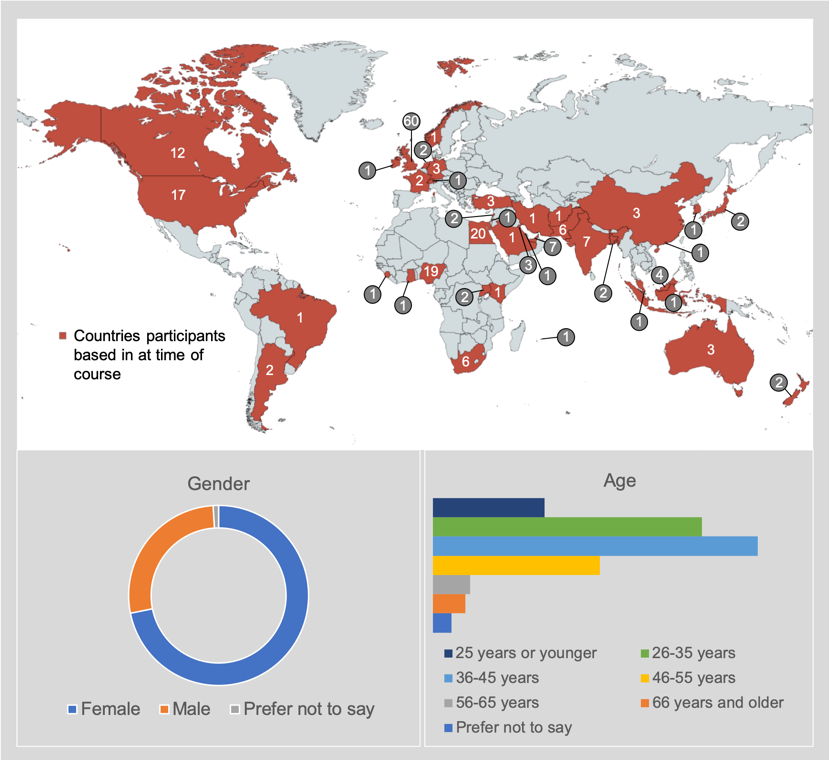

As an example of participant demographics, this is an overview of participants from trial 3 (i.e. participants in ‘The Fundamentals of Educational Dialogue’ MOOC).

208 participants from 40 countries enrolled in the course and completed the pre-course survey. The following figure was developed for the publication featured in Thematic Inquiry 2 (Brugha et al., 2024) to display participants’ demographics.

When asked about their experience with MOOCs, 74% of participants said that they were not experienced with MOOCs, while only 26% said that they had prior experience.

Their workplaces ranged as well:

- Charity or NGO funded school: 7%

- Elite or private school: 16%

- Low cost private school: 9%

- Public / state / government funded / charter / academy school: 30%

- Religious school: 25%

- Supplementary school (evenings / weekends): 4%

The design principles

Drawing on the findings, ten design principles were developed for scalable and sustainable online professional development course models and communities of practice that promote practitioner reflection, agency and empowerment, and that view educators as valuable creators and contributors to professional learning resources.

Design Principle 1: Integrate accountability mechanisms in the design of the course

Accountability mechanisms are needed for participants to consistently engage in and complete the materials. While retention continues to be a significant challenge for MOOCs, the learning communities afforded by the mechanical MOOC model should be leveraged. This model acts as a community hub in which learning communities can be easily derived and scaled as an explicit part of the course. Accountability can be enhanced through:

- Offering a mixture of live and self-paced options;

- Offering meaningful opportunities for participants to interact and collaborate;

- Establishing a relationship with participants.

Design Principle 2: Provide a balance of flexibility and structure in the design of learning pathways and materials

The varied backgrounds and prior experiences participants had using educational dialogue in their practice necessitated a flexible course design that is accessible for different settings alongside individualised needs assessments. This allowed for the selection of appropriate learning pathways with a ladder of support for participants to access as needed. The course materials and resources should also offer a blend of structure and flexibility with customisable options.

Design Principle 3: Offer opportunities for meaningful dialogue and collaboration amongst participants

Participants were keen to share their knowledge and learn from others in the course, yet there was poor engagement with most of the communication and collaborative features. This makes the role of the local facilitator integral in creating those dialogues within their own settings amongst the colleagues they intend to support and convene. Successful methods for encouraging dialogue and collaboration include:

- Having synchronous and asynchronous modes of communication explicitly as part of the course design;

- The research buddy system indicated a promising avenue for peer reflection, support and collaboration;

- Allowing space for participants to lead events themselves and functionality for them to plan and orchestrate this.

Design Principle 4: Incorporate reflective activities for both local facilitators and their colleagues

The course saw success through providing tools for learners that promote continued reflection and include ways that practitioners can continually reassess and adapt their practice. Reflective activities should be explicitly and strategically embedded in course videos, resources and activities, including the use of reflective journals or other related templates that can be adjusted based on the unique context of the participant. There should also be an adequate amount of time built into the course for participants to employ their reflections regarding the theoretical or practical materials in their settings.

Design Principle 5: Offer opportunities for participants to create and share artefacts

Participants in MOOC trials noted the benefit of creating research products relevant to their contexts, and also shared their desire for accessing learning from others through the use of a resource bank. Courses should provide functionality in which practitioners can build on the available resources and share adapted versions in a meaningful way. This refers to the local facilitator participants in the MOOC as well as the teachers that they intend to convene in their settings, in order to enable the growth of an educational dialogue community of practice that emphasises collaboration and the co-construction of knowledge.

Design Principle 6: Consider the role of the participant in shaping the learning environment

Collaboration with participants was actively and systematically conducted during the course design, implementation and evaluation, which resulted in a more relevant and engaging course and a stronger sense of agency and empowerment for the participants. The mechanical MOOC model builds on constructivist learning theories and emphasises the importance of participants in shaping their learning spaces. This should also include participants being given the opportunity to contribute to associated course-related research.

Design Principle 7: Position accessibility centrally in the design of the course

Access barriers includes challenges associated with infrastructure and internet connectivity, digital literacy and varied prior experiences with technology, and different levels of familiarity with educational dialogue. This is a common challenge for MOOCs, and a lack of access may further exacerbate a digital divide and continue to marginalise the global south. Through positioning accessibility as central during the course design process, many of these factors can be mitigated. The course benefited from requesting accessibility considerations during the registration process as well as capturing prior experiences taking online courses and concerns regarding accessing professional development online. This helped to ensure appropriate support methods were established.

Design Principle 8: Align the course model and platform with the pedagogy of focus (i.e. the pedagogy the course seeks to impart)

There is significant synergy between the model of the mechanical MOOC, the open source platform developed to host the course, the inquiry-based approach of the materials featured in the courses, and the principles and theory of educational dialogue. These components interact well to emphasise facilitating teacher agency through establishing a sustainable and scalable community of practice in which practitioners from a range of contexts can access resources to adapt according to their setting. The MOOC, T-SEDA and dialogic principles also all emphasise teachers as valuable creators and reflective professionals who learn through collaboration and connection of practice.

Design Principle 9: Be intentional regarding the future of the course and consider whether and how scaffolding should be reduced for future iterations

The underpinning theoretical framework of mechanical MOOCs posits that courses should not be run as traditional training structures with experts, but rather run by a course facilitator who comes secondary to the community in directing the learning. Success has been seen in other similar mechanical MOOCs whereby highly engaged prior participants (often referred to as ‘champions’) organised learning communities to direct their foci within the course. There will likely always be a need for a course facilitator to run live cohorts, and the data from this study support this, but the support from the course facilitator can be scaled back once the community of practice is more established. There was also success seen in the use of a multiple course model whereby practitioners begin with a fundamentals course to reflect on theory (Course 1), then engage in a more practical inquiry (Course 2), and eventually pedagogical leadership in their setting (Course 3). The expectation is that this results in an environment that progressively requires less facilitator support.

Design Principle 10: Build systematic monitoring and evaluation of the course into its structure

The course benefitted from integrating monitoring and evaluation in the course design in order to ensure that future iterations of the course were informed by the experiences of participants. Questions for participants should include details regarding agency, empowerment, access, equity, sustainability and scalability. These questions and evaluation processes should also require very little input from research staff, e.g. through the use of integrated survey software with (mostly) closed questions. It is imperative that the design of the research tools considers sustainability and scalability carefully, and can accommodate a larger participant base.

TIP: Researchers and course providers should consider articulating these and other design principles for course participants themselves. This should include how participants can leverage the design principle in order to enhance their experience and learning in the course. This can then be recalled during data collection to elicit their feedback regarding any further modifications required to the design principles.

Further design considerations

The following further design considerations have been summarised from interviews with sector specialists.

- Understanding the importance of ethos and culture and the need to foster an authentic community where participants feel included and respected.

- Prioritise simplicity and navigability in technology design. Through having technology components that learners are already familiar with, this can increase their capacity to engage in collaborative work and peer-to-peer dialogue.

- The ability to control one’s own space online via platforms like mechanical MOOCs can enable learner agency and contribute to forming a community of practice.

- Course design should include an intentional but not over-structured element for post-course collaboration between participants.

- The regulatory environment and amount of institutional support and alignment with the course pedagogy of focus and its delivery model deeply affect participants’ uptake of the materials and the implementation of those materials into their practice. Course designers should consider whether educators have support at their institutional and district level to spend the time on a course.

In addition to the design principles identified above, the importance of the role of the local facilitator continued to emerge as critical in discussions regarding scalability, sustainability and impact in these conversations. This relates back to the mechanical MOOC model and the focus on leveraging technology for enhancing community not only globally but also within the local settings of practitioners.

Further reading

For more information and details regarding the findings and the design principles, I recommend reading the following two publications, which I co-authored with CEDiR colleagues:

Brugha, M. & Hennessy, S. (2022). Educators as Creators: Lessons from a mechanical MOOC on educational dialogue for local facilitators. Irish Educational Studies 41(1), 225-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.2022527

Brugha, M. and Ahmed, F. (2023). Teacher professional development in educational dialogue: lessons from a massive open online course. Routledge Open Research, 2:15. https://doi.org/10.12688/routledgeopenres.17681.1