Case study 3: Equitable access to MOOCs for teacher professional development

Overview

This case study was developed in order to explore reach and equitable access to oTPD in further detail through analysing the perspectives and experiences of a selection of practitioners from the MOOC trials. This case study has not been published, however a version was submitted and accepted for presentation at a symposium at SIG 20-26 EARLI conference in September 2024 in Berlin. It is presented in a similar way to the previous findings and discussion sections to retain consistency in style.

Background

TPD is needed to develop and enhance educational dialogue in practice, and the use of online learning tools and courses such as MOOCs have the potential to scale support to more educators globally. Through oTPD, educators can access learning opportunities that are not available in their local contexts, and can connect with a wide range of practitioners in other settings (Dede et al., 2009). Possible affordances of oTPD include access to quality content in areas without in-person alternatives; flexibility of the course schedule to work around competing commitments; opportunities to collaborate and reflect with other practitioners globally; and in the case of MOOCs, this also includes a no- or low-cost model. In low-resource contexts, online learning also has the potential to increase the reach and access to quality TPD.

However, significant challenges remain in accessing these courses, which are often faced most by already marginalised populations. Barriers include the digital literacy required, difficulties in the translation and localisation of materials, and the level of learning that actually occurs (Liyanagunawardena et al., 2013; Major et al., 2018). MOOCs in particular have suffered from low retention rates and inflexible course content which cannot be easily contextualised by all participants. Importantly, these courses also cannot be completed or engaged with by individuals who lack consistent and reliable access to devices, internet connectivity and electricity.

Online education therefore risks widening existing inequalities (Dawadi et al., 2024; Gyamerah, 2020). For example, in the context of Nepal, Devkota (2022) indicates that inequalities in Nepalese higher education are reinforced through online education because of a lack of language, technical, and pedagogical support for marginalised learners. Inequalities in digital access and inclusion exist within and between countries, and significant barriers have been reported in enabling access to digital technologies (e.g. see Burns and Gottschalk, 2019). In MOOCs, this can result in particularly high attrition rates for already marginalised learners (Dziuban et al., 2018).

Having equitable access and digital inclusion at the forefront of an oTPD course’s design and facilitation is critical to mitigate these continued challenges. Access refers to which students are actually able to enrol in a course and equity ensures that the needs of all learners are met and that, “there is a concern with fairness such that the education of all learners is seen as being of equal importance.” (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2017, p. 7). Research on inclusive education has traditionally focused on students with special educational needs and disabilities, however the sector has begun to take a wider look at inclusion (Mezzanotte, 2022), which is the position that this case study takes. Broadly speaking, inclusion is “a process that helps to overcome barriers limiting the presence, participation, and achievement of learners” (Ibid, p. 7). Related to this, equitable access and digital inclusion strives for full participation by all participants regardless of background, and recognises the numerous resources necessary for this level of participation. Digital inclusion involves “leveraging digital tools to widen access and enhance the quality of teaching and learning for the purpose of delivering a fair and equitable education” (European Commission et al., 2021).

With the increasing popularity of oTPD opportunities, it is critical to consider who is able to access and meaningfully engage in online TPD, who is not, and the ways that equitable access and inclusion can be promoted through course features.

Aims

This case study explores the equity of enrolment and participation in the Educational Dialogue MOOC series. There is a clear need for further evidence and documentation of experiences regarding enablers and barriers to equitable access of online learning for educators, and their ability to engage in the course with cohort peers. This case study therefore asks three questions that have guided the research:

RQ1: What affordances can MOOCs provide to teachers globally in accessing an online forum of educators RQ2: What are the barriers to teacher participation? RQ3: What course and design features promote equity and inclusion in accessing online teacher professional development?

It is the objective of this case study to contribute towards a better understanding of how to form relevant, effective, and genuinely dialogic online spaces for practitioners to come together in a community of practice that is accessible to all educators.

Methods

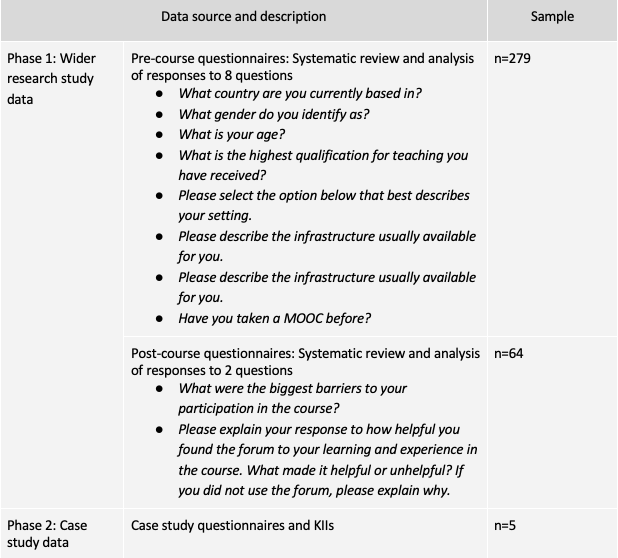

This case study builds on findings from the wider study. These courses were created to be relevant for a wide range of in-service school-level and higher education educators in varied geographies. Following initial analysis of questionnaire responses (279 pre-course and 64 post-course) and the formation of associated design principles, case study methodology (Hamilton, 2011) was utilised to explore the above research questions. In-depth questionnaires and interviews were conducted with five purposefully-selected participants from Iran (n=1) and Sierra Leone (n=4) who had participated in one or more of the course trials and were willing to share their experiences. The participant from Iran took the course independently, and the group of participants from Sierra Leone all worked in the same institution. The following is an overview of the data sources:

Responses to ten questions from the pre- and post-course questionnaires from the three course trials were analysed with the case study research questions as a guideline. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse responses to closed-ended questions, and inductive thematic analysis using constant comparison methods was used to analyse responses to open-ended questions. The results of the survey analysis regarding reach and access influenced the design of further case study data collection. Survey results are presented in Chapters 5.1 and 5.2 and so are not repeated in this section to reduce repetition.

In addition to utilising this wider data regarding the demographics of participants and accessibility affordances and constraints (as reported in Brugha and Hennessy 2022 and Brugha and Ahmed 2023), in-depth case study interviews and questionnaires (see Appendix K) were conducted with five participants. Semi-structured interviews and questionnaires were conducted with each of the five participants, which included two individual interviews (approximately 30 minutes each held on Google Meet), a group interview with three of the four practitioners from the Sierra Leone group (approximately 45 minutes held on Google Meet), and responses to five questionnaires (via word document attached to emails because of challenges associated with internet connectivity and filling out an online questionnaire). The interviews were conducted first and sought to elicit initial insights and reflections on issues regarding access and equity in the participation and completion of a MOOC for teacher professional development. These were followed by detailed questionnaires, which allowed the respondent more time to provide details regarding their contexts, their history with online learning and educational dialogue, how they define access to oTPD, affordances of oTPD for their settings, as well as barriers to access, participation and collaboration with course peers. This questionnaire also sought respondents’ recommendations to make oTPD more accessible and inclusive. Interview transcripts were transcribed and transferred to NVivo for coding. Top-down coding was conducted first and was based on Warschauer’s (2003) conceptual framework of resources that shape digital inclusion:

- Physical resources, which include access to appropriate hardware, reliable access to the internet, electricity and a physical space to study.

- Human resources, which include digital literacy, prior education and experience with the content, and self-regulated learning skills (Means et al., 2014).

- Social resources, which include facilitators, peers and colleagues.

This coding was cross-cutting for the three RQs. Other relevant information in the data was also considered to better understand specific affordances of MOOCs (RQ1), barriers to teacher participation (RQ2), and course features that support inclusion (RQ3). Emerging or open codes included affective aspects (for example, pastoral support, flexibility in course design, scaffolding in resource provision, etc.). New findings that emerged from the analysis of the case study data were documented and compared with existing findings from previous analysis from the wider study, documenting confirmation and counter-examples throughout.

Findings

Using Warschauer’s (2003) conceptual framework of resources that shape digital inclusion, findings are presented and discussed by resource category, drawing on the experiences and insights shared by course participants. Note that demographics of participants are presented above in Chapters 5.1, 5.2, and 6.2 and are therefore not repeated here.

Physical resources

According to Warschauer (2003), to effectively engage in online learning, participants need access to appropriate hardware, reliable access to the internet, electricity, and a physical space for study. Availability of infrastructure emerged as critical during the case study interviews, particularly with the Sierra Leone team. This included connectivity and bandwidth infrastructure as well as reliable and consistent access to devices. This was described by participants as a significant barrier in accessing oTPD, including for this MOOC series:

“In some parts of the world, like rural areas especially in my setting, there may be challenges with poor internet connectivity and unstable electricity, making it difficult to have consistent online engagement.” (Kabiru, Sierra Leone)

“My ability to fully interact with the course contents and take part in live activities was hampered by technical problems, such as sluggish internet connections.” (Foday, Sierra Leone)

Human resources

In addition to challenges associated with accessing devices and connecting to course sites, participation in the MOOCs required a level of digital literacy to navigate online learning platforms efficiently and participate in the various features. As articulated by Kabiru (Sierra Leone): “Some teachers may face challenges in adapting to online learning platforms if they lack the necessary technological skills or familiarity with using these tools.”

To mitigate this, the course design included the site navigation being intentionally simplified, and the development of a comprehensive user guide for participants to access to make troubleshooting technical issues easier. However, soft skills were also required to participate in the collaborative components of the course. Kabiru (Sierra Leone) explained:

One challenge is the difficulty some teachers may face in familiarising themselves with the technology and using the functions of the platforms like Zoom to join breakout rooms. Additionally, if the breakout room structure is not well-defined, it may hinder active participation. For example, if the agenda does not provide everyone with an opportunity to contribute to the conversation, some teachers who are not accustomed to online discussions may find it challenging to engage effectively.

Kabiru offers a design recommendation here, which is to provide structure that explicitly enables inclusive participation and recognises the potential fears associated with participating in synchronous as well as asynchronous online dialogue for some participants.

The varied levels of familiarity with educational dialogue also necessitated a ladder of support for participants to access. Case study participants all had an underlying investment in educational dialogue and a clear initial interest in expanding their knowledge on the subject. This gave them the confidence to engage in the interactive features of the course, but they noted that additional support should be available for participants who do not have familiarity with the content. This included access to a wide range of resources that can be relevant for varied settings as well as tools that can be easily contextualised. As noted by Kai (Sierra Leone), this use of a resource bank “enables teachers to explore diverse topics and gain new insights into teaching practices.” Participants also agreed that having downloadable tools that could be easily adapted to different settings were critical. This could help mitigate the challenge identified by Miriam (Sierra Leone): “The challenge was that the MOOC format necessarily is quite general so if one is in a slightly obscure context like ours, then it is harder to see how the learning might be contextualised.”

Self-motivation and time management skills deeply affected participants’ abilities to sustain their engagement in the materials and complete the course, as identified by participants in the questionnaires and interviews. As Foday (Sierra Leone) reflected: “I found it challenging to set aside enough time to finish readings, watch videos, or actively participate in discussion forums or live events because of the demands of my job, my personal obligations, or my conflicting schedules.” The level of flexibility within the course structure appeared to both resolve this challenge whilst simultaneously exacerbating it. Participants agreed that flexibility within the course design was needed in order to allow for participants’ competing priorities and scheduling conflicts, however this needed to be balanced with accountability mechanisms to ensure that momentum was maintained. Kai (Sierra Leone) summarised this as follows: “Online professional learning allows teachers to engage in learning at their own pace and at a time that is convenient for them, making it accessible for busy teachers… [however,] some educators may struggle with staying motivated and organised in a self-paced environment.”

Social resources

Social resources that were necessary for participants to access and engage in the course materials included myself as the course facilitator, cohort peers, and institutional support including that of participants’ colleagues. Accessing these social resources within the MOOC was consistently cited as the most influential factor motivating participants to take and engage in oTPD, and to sustain the impact from oTPD. This went ahead of accreditation, accessing content they could implement, and fulfilling professional development obligations. Similarly, when asked about other examples of highly effective and impactful professional learning opportunities (online or otherwise), respondents provided examples of TPD that were focused on collaborative learning.

There was significant interest from all participants who submitted pre- and post-course questionnaires in participating in a community of practice in which experiences related to dialogic practice and specific tools can be shared. On an international level, this included “peers from different locations [who] share ideas and engage in discussions to enhance their professional growth” (Kai, Sierra Leone).

Kabiru (Sierra Leone) specifically noted the use of the discussion forum for this:

When considering online courses, certain components are important to me. One vital component is a discussion forum. It allows participants to engage in dialogue, share experiences, and ask questions. This collaborative space provides valuable insights and perspectives from fellow educators, enriching the learning experience. It also allows for clarifying concepts and seeking further explanations… engagement and access to course instructors are also important.

This desire for collaboration also extended beyond the course and into local settings. When asked what it was that attracted him to the MOOC, Foday (Sierra Leone) responded: “First, it was accessible. More importantly, I saw the MOOC as a useful learning opportunity for me which I hoped to share with my teachers and people in my department.”

However, the level of access to peers as social resources differed between participants and some were unable to fully participate in the discussions taking place, for example because of language barriers or inexperience with the course content. Further challenges collaborating with cohort peers are summarised by Foday (Sierra Leone):

Time zone differences and technology difficulties are what I believe are obstacles to conversing with others in a global online course. It takes approaches like allowing for multiple time zones, allowing participants to go at their own pace, and offering technical assistance to get over these obstacles.

Foday (Sierra Leone) offers recommendations for how these barriers can be addressed:

Relevance, a supportive online community, a secure and polite atmosphere, clear guidelines, scheduling, flexibility, facilitator assistance, and technological competence are some characteristics that affect a teacher’s participation in online teacher-to-teacher interaction.

Kai (Sierra Leone) added that being recognised in the dialogue (e.g. through responses or likes) can also help address some of the barriers: “Recognition is key. Teachers will participate in any dialogue if they are recognised. If you are not recognised in any dialogue, we will be bored and not be paying attention.”

Respondents also recognised the challenges of an exclusively online course: “It can be challenging to build relationships and engage in spontaneous discussions” (Kai, Sierra Leone). His colleague, Foday (Sierra Leone) added: “the absence of the instant personal interaction present in face-to-face settings, which hinders participation and makes it difficult to forge genuine connections with teachers and peers, was another difficulty for me.” Ghasem (Iran) agreed: “in face-to-face we can create more effective connections… the biggest challenge I faced while taking these courses was connecting with other learners”. Ghasem went on to explain his experience: “in the MOOC, the relationship between learners was not strong but our facilitator had made a strong connection”. Having this connection with a course facilitator was impactful for his journey throughout the course trials.

Having opportunities to engage in dialogue and exchange thoughts and tools with other practitioners was considered to be both a requirement and outcome of access. Participants noted that despite encountering challenges in participating in online dialogue via the forum and live events due to language barriers and lack of confidence, they were also driven by contributing to and being part of a global community of practice: “We should work on relationships with the members of MOOC as a community with a dialogue culture. We need a dialogic space between teachers in the world. We should have a plan for follow-up” (Ghasem, Iran).

Another component of social resources for digital inclusion are local colleagues and institutions. Most participants from the wider course data noted the importance of support from their settings and the alignment of the course with their institutional priorities, such as the Sierra Leone team who all agreed that dialogic pedagogy was aligned with their institutional and current government foci. However, Ghasem (Iran) articulated educational dialogue as being in opposition to his setting, which he described as using traditional practices. He sought the course to connect with other like-minded practitioners.

Discussion

These findings offer a range of implications for course designers and facilitators, which are discussed within five themes and address RQ3. Each theme can be leveraged to improve equitable access and digital inclusion in similar oTPD environments in consideration of the three resource categories from Warschauer’s (2003) conceptual framework. It is clear that technology is not culturally neutral, and there is a risk of continued marginalisation and inequity through users blindly importing ‘western’ paradigms into international contexts. And while it is likely impossible to remove cultural influences from a course’s design, these five areas can be leveraged to mitigate those factors.

First, the inclusion of representative participant voices involves collaboration with course participants from the course conception through its design, launch, facilitation and evaluation. It is clear that understanding learners’ contexts through involving their voices in the design of the course is critical. This views the learner as an expert in their field and setting, and recognises their critical role in driving change. As articulated by Gunawardena (2020),

It is crucial that local actors who understand the sociocultural context identify the needs for which they want the project, design the process of change they envision, and manage and evaluate it… Local actors must own the project if it is to become sustainable. (p. 7)

This results in a more relevant programme and content because it has involved educators in decision-making. It also ensures that the learning (and materials) can be localised, as the unique needs of the participants and their settings have already been captured.

Related to participatory approaches, the second theme argues that being community-led and driven through opportunities for meaningful collaboration and learning partnerships creates a more accessible avenue to shaping the course.

Third, reflective and adaptive course materials and tools should be available that guide participants in metacognitive exercises and content. The literature supports this; for example, Escobari et al. (2019) indicate that marginalised learners who have experienced disempowerment and who internalise a narrative of self-doubt benefit from interventions that focus on changing the way they think and reflecting on their thinking in addition to content-related interventions. Reflexive activities should not be reserved for only the learner but rather, the facilitator should also engage in a continuous process of reflection and inquiry and confront bias in a direct way. As recommended by Gunawardena (2020), courses would do well to design for cultural inclusivity, not neutrality. To do this, it is critical for course designers and facilitators to reflect continuously on their own cultural biases. Positionality was a central consideration for the wider research study throughout all research phases (see Section 3.5 for an overview of the process and documented reflections). This was coupled with reflective exercises incorporated into the course structure to encourage participants to undertake a similar process of self-reflection.

Fourth, flexibility in program structure can help marginalised learners succeed. Escobari et al. (2019) indicate that adult learners are especially likely to face time, financial and familial constraints when returning to formal study. The MOOC series benefitted from offering flexibility where it mattered most to participants, whilst also acknowledging the importance of maintaining momentum through the inclusion of strategic accountability devices.

Fifth, providing scaffolding to participants through a ladder of support for both digital literacy as well as content-related support. While most MOOCs do not list prerequisite knowledge or experience, there appears to be a discrepancy between the level of the content in the course and students’ capabilities. Related to this, resources should also be examined for inequities as well that are perpetuated through the language of the course, citations, resources, etc. As articulated by Knupfer (1997), “inequities that result from the practice of instructional design often go unrecognised because they emerge not just as a result of what has been done, but also as a result of what has been left undone”.

Conclusions

This case study explored: (a) the affordances that MOOCs can provide to teachers globally in accessing an online forum of educators; (b) the barriers to participation; and (c) which course and design features promote equity and inclusion in accessing online teacher professional development.

Findings revealed equity issues across all three resource areas including reliable access to devices and internet connectivity, varied levels of digital literacy and prior experience with both online learning as well as the concepts associated with educational dialogue, and lastly with accessing the course’s community and collaborative activities and events. Warschauer’s (2003) conceptual framework was leveraged to discuss ways to address these concerns and increase equitable access to online learning through course design and facilitation strategies. These strategies include: (i) positioning participant voices as central in course design; (ii) providing avenues for participants to meaningfully collaborate with their peers (both on the course and locally via a local facilitator or learning communities); (iii) incorporating reflective activities for both participants and facilitators; (iv) ensuring a flexible course structure; and (v) providing scaffolding for digital literacy and course content.

While accessibility was positioned as central in designing the MOOC series, access remained a significant challenge for many participants. The course objective was not to reach the most marginalised communities of learners, but rather to trial a prototype that could convene an online community of practice; the conflict being that in so doing, it inadvertently likely excluded the most marginalised learners. Even those participants who had prior experience with online professional development and with educational dialogue but experienced one or more accessibility constraints in the above themes did not complete the course.

There is a clear case for oTPD to be used to strategically enhance access to effective professional learning. Participants shared positive experiences alongside challenges, which are aligned with wider sector evidence. Continued research is needed that features the real, lived experiences of participants in global oTPD from marginalised communities. Furthermore, inclusivity and accessibility in oTPD stands to be better defined as it relates to these contexts. There continues to be a lack of understanding of the depth of inclusivity, which results in a simplistic definition and therefore an inability to adequately address its weaknesses. These were also limitations in the wider course series, which additionally could not track individual experiences. More data is needed, particularly as it relates to classroom-level impact as well as institutional and community-level support. A more in-depth case study that draws on multiple contexts would be helpful and may increase the generalisability of associated findings.